Kirchner: Darkness Approaching

On the 15th of June 1938, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner held a pistol to his chest and pulled the trigger, twice. The twin shots would end the life of Germany’s greatest expressionist.

Kirchner had been struggling with a serious level of depression for some time, troubled by the progressive bastardisation of Germany under Nazi rule. The annexation of Austria a few months before his death, combined with the swirling rumours of a potential invasion of his new home of Switzerland, proved to be especially disturbing to the artist. A further relapse into an opioid addiction earlier in the month and the retraction of his marriage proposal to partner Erna, only aid to further illustrate the painter’s inner turmoil.

In this piece, we are going to look at Kirchner’s final self-portrait. The painting tells the story of a man disturbed, a darkening world and an unwavering sense of romantic regret.

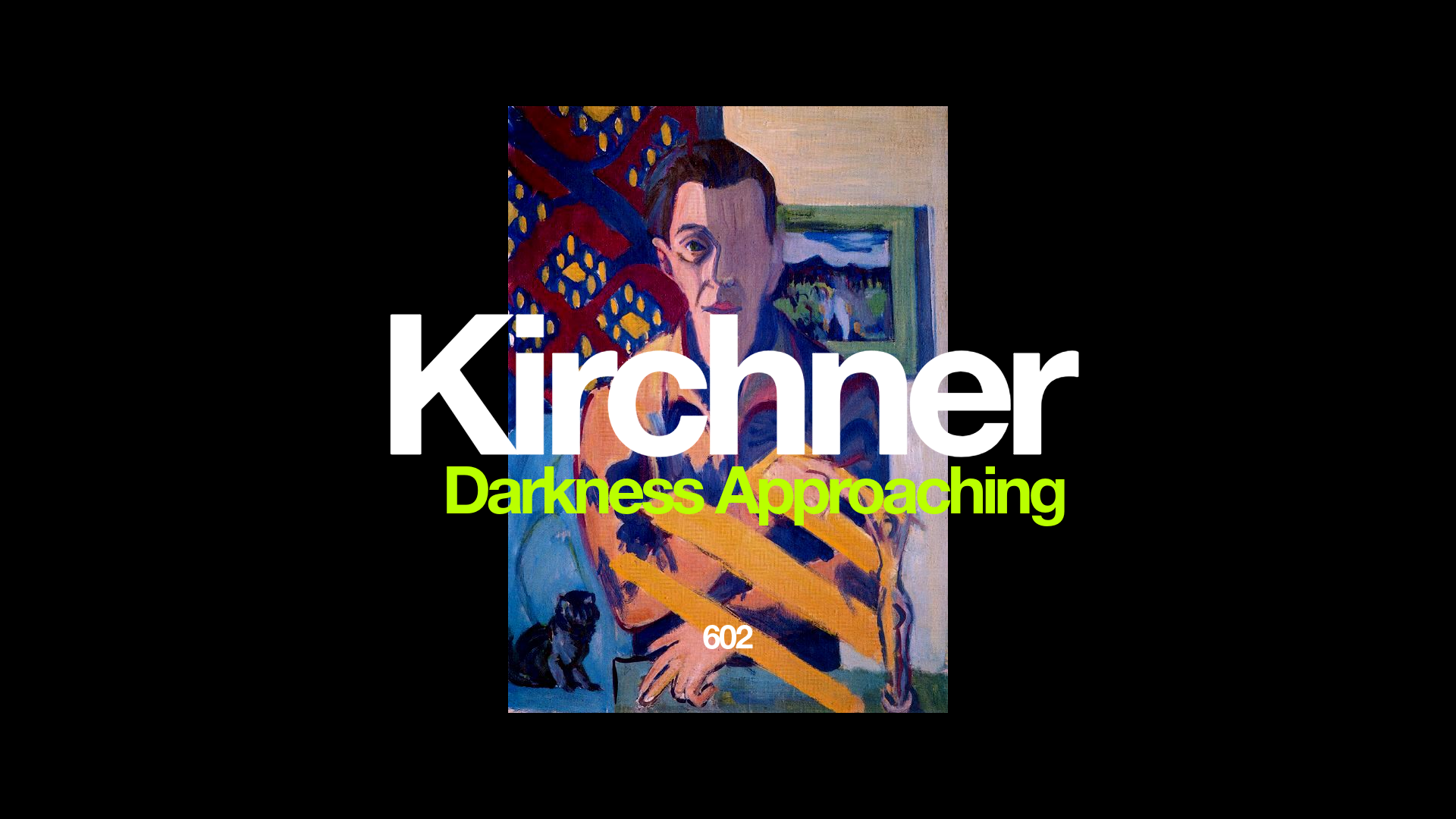

‘Self-Portrait’ - Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - 1937/38

The piece is unarguably bipolar, not only in its meaning, but also its composition. A dividing line runs vertically down the centre, leaving two distinct sides.

On the right, we see Kirchner’s present; a beautifully-realised alpine scene hangs over the shoulder of the artist, hinting at his love for the home he resides in with Erna close to the town of Davos. After his time living in the cities of Munich, Dresden and Berlin, the sloping hills, bucolic meadows and idyllic villages would’ve seemed like an oasis of calm for a turbulent mind. In the foreground we have a model of the female form, indicative of his fiancée Erna Schilling. Her figure emanates a glow of cadmium yellow which fights to bring light and structure to the artist’s life. Kirchner produced many portraits of Erna over his career, celebrating her role as his love and muse, yet here she’s depicted as a lifeless mannequin, as though he feels he’s keeping her hostage in the countryside after she moved from Berlin to live with him.

The mannequin’s hands are raised as if she’s trying to enter the eyeline of the artist, vying for his attention. The face she’s reaching out to doesn’t exist however; it’s blurred, cast in an all-consuming shadow. The mannequin’s glow tries, but falls short of the man she loves, suggesting he’s too far gone, he’s already dead.

The lighter right-hand side is offset by a much darker left. A curtain hangs behind the artist, the blue so powerful it engulfs the chair below in its cold hue. If we are to think of the right side as being representative of his present in Switzerland, then this left side is representative of the life and the country he left behind. Upon the curtain, deep red swastikas are sewn, their size and prominence unavoidable, all-consuming. The black cat, a regular subject for Kirchner in his Berlin era, stands on the couch and shows how the artist holds a sense of hope, however small, that Germany could return to the one he once loved. With hindsight we know of course that this hope was misplaced, the violent juncture of Kristallnacht would follow a few months later followed by the beginning of the Second World War the following year. The fear Kirchner felt is strewn across his face; the left side lit brightly by dread, the right clouded in angst.

The piece acts as an allegory for a truly human behaviour, being unable to focus on the good of the present due to an asphyxiating obsession with the past. The mind of a troubled man is laid out on canvas for all to see, each stroke in oil is meaningful as if he knew it could be his last.

For the eighty or so years since his death, the story of a suicide by two pistol shots to the chest was widely accepted. However, in 2021, through an investigation involving firearms experts, this account was thrown into doubt. A lack of burns to the skin and clothing combined with the diminutive size of the holes were two reasons cited in favour of a theory that the shots must’ve been fired from a further range.

In spite of the doubt these accounts shed on the records of his untimely demise, the level of turmoil in his life shouldn’t be questioned. Kirchner was a man troubled by the past, the present and the future, a man whose darkness outweighed the light in his life.

“His life had completely derailed: depression, sickness, thoughts of death, and attempts at drug withdrawal and the completely surprising decision to take back his marriage proposal were all clear warning signs.”

- Germanisches Nationalmuseum